Bruce Mountain, Victoria University

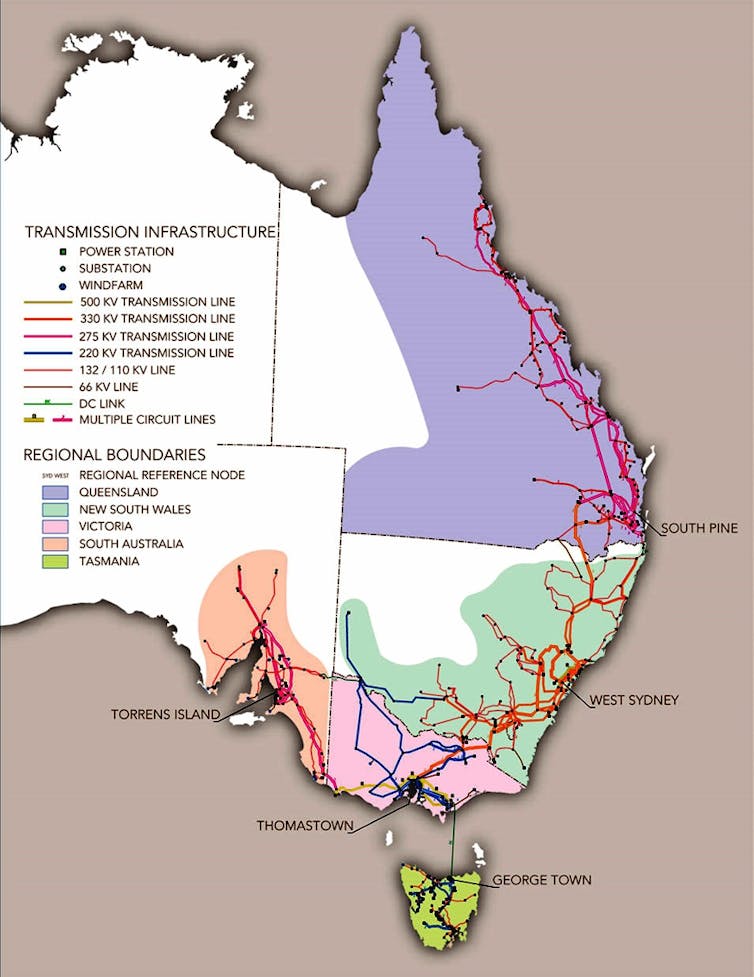

It has been more than 20 years in the making, but there is now a new order in Australia’s grandest (and most problematic) example of cooperative federalism, the National Electricity Market. Not completely national (it excludes Western Australia and the Northern Territory), it links most towns east of Port Lincoln and south of Port Douglas so that, in theory, electricity produced near any of them can be used anywhere else.

This year first Victoria, and now NSW, have brought the development of their transmission and generation systems back under their own control.

Victoria set the ball rolling earlier this year with legislation to take back the power to plan and deliver new transmission.

In November in its first major use of the new laws it announced the procurement of a 300 megawatt battery near Geelong. Just three years ago a battery this size would have been three times bigger than the biggest in the world.

NSW followed with legislation in November to create new authorities to plan and contract for the development of what it expects to be A$32 billion worth of new transmission, generation and storage facilities over the next 10 years.

In both states the legislation obtained widespread support in parliament.

Why they’re bringing electricity home

The reasons are political and economic. Politically, reductions in the costs of wind and solar generation has meant decarbonisation is increasingly seen as a way to cut electricity prices.

But in both states a small number of privately-owned coal generators dominate production. Their owners have little interest in cutting the value of their plants by bringing on (renewable) replacements.

In addition, notwithstanding the privatisation of generation and the creation of the National Electricity Market, voters have continued to look to state ministers to decarbonise the grid, keep the lights on and get prices down.

The arrangements that governed the market left state governments with responsibility but no control.

Economically, while the creators of the market 20 years ago recognised that separating generation from transmission could undermine the coordinated development of both, they were persuaded that the gains from competition in generation would deliver more value.

These days, in the context of the rapid switch from a small number of ageing coal-fired generators to a larger number of new renewable-powered generators that need access to transmission, coordination between generation and transmission has become more important.

And the ability of suppliers to site generators in multiple locations (including on the roofs of factories and homes) rather than near coal mines which might be in other states, has made it easier for state governments to plan for self-sufficiency.

What state power will look like

Much remains to be worked out, but the direction is clear. State governments will increasingly plan and contract for the delivery of generators and storage services themselves.

They will also be facilitating, and perhaps to some degree funding, the development of the transmission system.

Most of the assets will continue to be privately owned, but producers and storage providers will increasingly be contracting with states for access to their markets rather than competing against other producers in the national market.

The companies that own coal generators and supply to their own retail businesses will be the big losers.

Their generation will be rendered uncompetitive by wind and solar farms, and they will be forced to buy from them (and perhaps even from generators owned by state governments) in order to keep customers.

This is a much tougher business model than the one they have become used to.

But it isn’t right to say the clock has come full circle; that we are going back to the bad old days of (often self-serving) state electricity commissions.

There are certainly similarities, and a risk of governments planning and procuring badly and forcing customers to pay for their failures.

But much is different. Customers are able to choose who they buy electricity from and are able to make some of it themselves if they want to.

This ability to choose exerts a powerful discipline. It is assisted by developments in production and storage and access to data that presents opportunities that could not have been imagined five years, much less 20 years ago.

There are plenty of new opportunities waiting to be explored.

Bruce Mountain is the director of the Victoria Energy Policy Centre at Victoria University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4.5